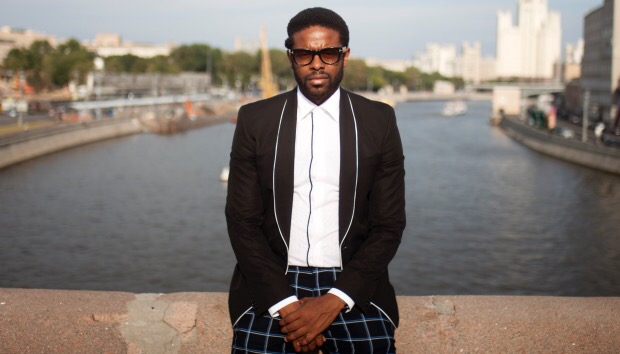

There is truly something special about Adrian Younge’s music. The methodical, upper echelon, level of quality and attention to detail in his unique blend of the late 60s to early 70s sound is a standard that not many musicians these days can live up to. I first became deeply immersed in his work after stumbling across Something About April back in 2012 and have been an avid listener from that point forward. For any crate digging sample freak, his music is a no-brainer — a stark departure from the direction that contemporary urban mainstream music has taken. With all it’s vintage aesthetic, though, it comes off as fresh and new. Music that’s meant to be experienced.

He rose to notoriety in many hip-hop circles after he collaborated with Ghostface Killah for the first of two installments of Twelve Reasons To Die, put in work on Jigga’s MCHG [on the song “Picasso Baby], and was the sample bank used by Primo for the Royce 5’9 collaborative project PRhyme. Not to mention his work on Kendrick Lamar’s “untitled 06.” The crossover into hip-hop — and his work alongside Ali Shaheed Muhammad of ATCQ on his label Linear Labs — has grown his very focused and adoring fan base.

Adrian has more than established himself, and as such, has decided to take a leap with his latest project, The Electronique Void: Black Noise. “I wanted to make an electronic album that [actually] is an electronic album. There was a time when you heard the concept of electronic music, and you didn’t think of the notion of EDM. It’s not EDM; this is straight electronic music, but it’s electronic music recorded in the way our pioneers did it, using the same kind of equipment and techniques, so it sounds different.”

Adrian took some time out to chat with us about The Electronique Void: Black Noise, his creative process, his label, his record store, and much more. Check out the interview below, and be sure to grab the album for yourself. Also — he and Ali Shaheed Muhammad scored Marvel’s “Luke Cage,” so now you know!

Let’s talk about the new album — it’s quite different than your other work, what made you explore this new avenue?

Well, I’ve always wanted to do an electronic album. The thing is, I had to wait for the right time because I had to establish who I am first. I’m a composer/producer that loves cinematic music from the late 60s early 70s, more particularly from the period of ’68 to ’73. So this has been brewing in me for a while, and I just finally said you know what, it’s time to go in. So I’m hanging out with NoID a lot — that’s one of my good friends — and he was just rekindling my affinity with analog synthesizers, and I just said you know what? It’s time now. I’ve got to do this project. So I hooked up with one of my good friends who’s also in my band, and he’s like a mentor to me, Jack Waterson, to put this together. I said, ‘Handle the dialogue, this is the concept, and I’ll handle the music.’ So he controlled the discourse — the dialogue. It’s a dark, twisted story where we’re explaining that love is a concept, it’s not something that’s finite. You can’t determine all its variables, but you know it’s there. So, it’s a story about ‘how to love.’

How do you come up with the concepts for your albums?

A lot of times it’s more of a precognitive, intuitive thinking type of mindset, where I know I want to do another project and then something just jumps in my head that just inspires me so much that it inspires music. I make music with parameters and limitations, meaning I like to create boundaries I have to stay within and make something within those boundaries. So for example on this album, I didn’t play any bass guitar, no piano — everything was analog synth. No horns, no flutes, and the only thing as far as an organic instrument is a drum set, and I’m singing into a vocoder while I play. So those are the only two love elements, so I wanted to prove to myself that I could make an album not relying on my key instruments.

Your music is very meticulous, and it has an intense thought process behind it. It also has a particular type of sound. So what drives that? Do you have a lot of influences?

Well for me, all my influences come from old records. I tell people I don’t listen to new music. New music to me is old records I haven’t heard. So that’s where all my influences come from, and the thing is that today, people don’t pay attention to detail as much as they used to, and my fan base is a very intelligent fan base. It’s arguably academic. My fan base needs a little more, so I like to cater to those kinds of people because that’s the kind of person that I am. So there’re people out there that think the music of the past was great, but that’s gone because people don’t make music like that anymore, but it’s just not true. You can decide not to cut any corners, and just basically take a stance that you’re not going to defer to recording in a way that takes away from yourself. A lot of people want to use pro tools and all that, which is great, but for what I do you have to use tape, you have to use real instruments.

There’s a lot of musicians out there that want to do what I do, but they don’t want to put in the work and spend the money to get a great, classic analog sound to make more music. So all of this pushes me, because when I hear people that appreciate what I do, like yourself, it’s my inspiration. I always tell people I make music for the audience in my head, and when other people like my music, it’s very pleasing, inspiring, and motivating, because I feel as though what I’m doing is something that is meant for a select few. Since the vast majority of people like top 40, and I hate top forty. So my inspiration comes from the recognition I get from like-minded individuals, and also my mission to always try to outdo myself.

Personally, I like to collect vinyl, and I’m into vintage music. I got into it because I like the elements and samples of [hip-hop] records — do you maybe see yourself as being a bridge to vintage music or old jazz?

Absolutely. Just as hip-hop serves as a conduit to the past and culture, I want to act as a conduit to the past for our culture, as well as younger people searching. So hip-hop introduced us to The Breaks, and I want to introduce people to The Breaks and hip-hop, so I look to serve as a conduit to the past.

I’d love to know your role in the PRhyme album. Because it’s produced by Premier, but you brought all the samples and little elements. Could you maybe explain how that works?

Premo sampled my entire catalog to make PRhyme, and this was Royce da 5’9″s idea because at that time Premo knew of me, but he didn’t want to limit himself to sampling one person. A lot of people don’t realize how difficult it is to make a full album sampling one person. He started on one track, and he went to the next, and he went to the next, and he got into a real rhythm, and just really made classics, and to me, it was an honor because having Premo sample my music makes my music better. It makes me listen to my music in a different way, so it’s special for me. And I love Premo, and I love Royce. Those are my really good friends.

Can you tell me a little bit about Linear Labs, and the ideology behind it, and some of the artists that are a part of it?

Linear Labs is a label that I run, and it serves as a record label that addresses the desires of the tailored mind. People that want something more bespoke. It’s more of a handmade artisan approach to the crafting of music, so everything on Linear Labs is all on tape, all live instruments, and recorded in the way that they would have done yesterday, but with a modern sentiment. I’m never the kind of guy that wants to merely rehash old music, I always want to something that when you hear it, there’s something fresh about it, and that’s the mantra of Linear Labs. So, on Linear Labs we have an artist, Loren Oden, that’s going to be releasing a solo album pretty soon. We have Ali Shaheed Muhammad from A Tribe Called Quest, him and I are releasing an album called The Midnight Hour next year.

And it’s just a bunch of different artists, but it’s more so a boutique outlet for stuff that I like.

You own a record store as well, right?

Yeah, the record store is called The Artform Studio, and it’s a record store and hair salon that is owned and operated by myself and my wife. Right now we’ve moved locations, so we’re down for about two months, then we’ll be back open in Los Angeles.

That’s incredible. I can only imagine that you have amazing records there. With your music and your taste in music…

Oh yeah, dude. It’s great.

And as well, something I found interesting on your Wikipedia page is that you’re an entertainment law professor.

Yeah, I did that for three years, and then when music took over my life I didn’t have time. So I don’t do that anymore, but that’s definitely on my resume.

The model that’s on your Something About April II cover, Logan Melissa, has the coolest Instagram ever. What’s your relationship with her?

She’s been a good friend for a while. Wax Poetics approached me and said, ‘You need to check this girl out. She’d probably be a good candidate for your record cover.’ Because she was going to start writing for them – she’s breathtaking, but she’s very smart, too. We met, and we just hit it off. She’s like an extension of myself as far as visually, because she gets everything I want to do.

Anything you’d like to leave us with?

I wanted to make an electronic album that [ is] is an electronic album. There was a time when you heard the concept of electronic music, and you didn’t think of the notion of EDM. It’s not EDM; this is straight electronic music, but it’s electronic music recorded in the way our pioneers did it, using the same kind of equipment and techniques, so it sounds different. I want it to be a piece that hopefully becomes a classic.